Choco languages

| Chocoan | |

|---|---|

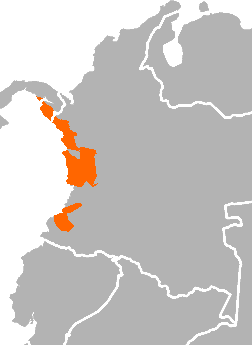

| Geographic distribution | Colombia and Panama |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | choc1280 |

| |

The Choco languages (also Chocoan, Chocó, Chokó) are a small family of Native American languages spread across Colombia and Panama.

Family division

[edit]Choco consists of six known branches, all but two of which are extinct.

- The Emberá languages (also known as Chocó proper, Cholo)

- Noanamá (also known as Waunana, Woun Meu)

- Anserma †

- Arma † ? (unattested)

- Sinúfana (Cenufara) † ?

- Caramanta † ?

Anserma, Arma, and Sinúfana are extinct.[citation needed]

The Emberá group consists of two languages mainly in Colombia with over 60,000 speakers that lie within a fairly mutually intelligible dialect continuum. Ethnologue divides this into six languages. Kaufman (1994) considers the term Cholo to be vague and condescending. Noanamá has some 6,000 speakers on the Panama-Colombia border.

Jolkesky (2016)

[edit]Internal classification by Jolkesky (2016):[1]

(† = extinct)

- Choko

- Waunana

- Embera

- Southern

- Northern

Language contact

[edit]Jolkesky (2016) notes that there are lexical similarities with the Guahibo, Kamsa, Paez, Tukano, Witoto-Okaina, Yaruro, Chibchan, and Bora-Muinane language families due to contact.[1]

Genetic links between Choco and Chibchan had been proposed by Lehmann (1920).[2] However, similarities are few, some of which may be related to the adoption of maize cultivation from neighbors.[1]: 324

Genetic relations

[edit]Choco has been included in a number of hypothetical phylum relationships:

- within Morris Swadesh's Macro-Leco

- Antonio Tovar, Jorge A. Suárez, and Robert Gunn: related to Cariban

- Čestmír Loukotka (1944): Southern Emberá may be related to Paezan, Noanamá to Arawakan

- within Paul Rivet and Loukotka's (1950) Cariban

- Constenla Umaña and Margery Peña: may be related to Chibchan

- within Joseph Greenberg's Nuclear Paezan, most closely related to Paezan and Barbacoan

- with Yaruro according to Pache (2016)[3]

Vocabulary

[edit]Loukotka (1968) lists the following basic vocabulary items for the Chocó languages.[4]

| gloss | Sambú | Chocó Pr. | Citara | Baudo | Waunana | Tadó | Saixa | Chamí | Ándagueda | Catio | Tukurá | N'Gvera |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| one | haba | abá | aba | aba | haba | aba | abbá | abba | abá | |||

| two | ome | ume | dáonomi | umé | homé | umé | ómay | tea | unmé | |||

| three | ompea | umpia | dáonatup | kimaris | hompé | umpea | ompayá | umbea | unpia | |||

| head | poro | poro | achiporo | púro | boró | tachi-púro | boró | bóro | buru | porú | ||

| eye | tau | tau | tabú | tau | dága | tau | tau | dáu | tow | dabu | tabú | tapü |

| tooth | kida | kida | kida | kidá | xidá | kidá | chida | chida | ||||

| man | amoxina | mukira | umakira | emokoida | mukira | mukína | mugira | mohuná | mukira | |||

| water | pañia | paniá | pania | pania | dó | pania | panía | banía | puneá | panea | pánia | |

| fire | tibua | tibuá | xemkavai | tupuk | tupu | tubechuá | tübü | |||||

| sun | pisia | pisiá | umantago | vesea | edau | vesea | áxonihino | umata | emwaiton | humandayo | ahumautu | |

| moon | edexo | édexo | hidexo | xedeko | xedego | edekoː | átoní | edexo | heydaho | xedeko | xedéko | hedeko |

| maize | pe | pe | paga | pedeu | pe | pe | bé | pe | ||||

| jaguar | imama | ibamá | ibamá | imama | kumá | pimamá | imama | imamá | imamá | |||

| arrow | enatruma | halomá | halomá | sia | chókiera | umatruma | sía | ukida | enentiera |

Proto-language

[edit]For reconstructions of Proto-Chocó and Proto-Emberá by Constenla and Margery (1991),[5] see the corresponding Spanish article.

See also

[edit]- Embera-Wounaan, who speak the Choco languages, Embera and Wounaan

- Quimbaya language

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Jolkesky, Marcelo Pinho De Valhery. 2016. Estudo arqueo-ecolinguístico das terras tropicais sul-americanas. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Brasília.

- ^ Lehmann, W. (1920). Zentral-Amerika. Teil I. Die Sprachen Zentral-Amerikas in ihren Beziehungen zueinander sowie zu Süd-Amerika und Mexico. Berlin: Reimer.

- ^ Pache, Matthias J. 2016. Pumé (Yaruro) and Chocoan: Evidence for a New Genealogical Link in Northern South America. Language Dynamics and Change 6 (2016) 99–155. doi:10.1163/22105832-00601001

- ^ Loukotka, Čestmír (1968). Classification of South American Indian languages. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center.

- ^ Constenla Umaña, Adolfo; Margery Peña, Enrique. (1991). Elementos de fonología comparada Chocó. Filología y lingüística, 17, 137-191.

Bibliography

[edit]- Campbell, Lyle. (1997). American Indian languages: The historical linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

- Constenla Umaña, Adolfo; & Margery Peña, Enrique. (1991). Elementos de fonología comparada Chocó. Filología y lingüística, 17, 137-191.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. (1987). Language in the Americas. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Gunn, Robert D. (Ed.). (1980). Claificación de los idiomas indígenas de Panamá, con un vocabulario comparativo de los mismos. Lenguas de Panamá (No. 7). Panama: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.

- Kaufman, Terrence. (1990). Language history in South America: What we know and how to know more. In D. L. Payne (Ed.), Amazonian linguistics: Studies in lowland South American languages (pp. 13–67). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70414-3.

- Kaufman, Terrence. (1994). The native languages of South America. In C. Mosley & R. E. Asher (Eds.), Atlas of the world's languages (pp. 46–76). London: Routledge.

- Loewen, Jacob. (1963). Choco I & Choco II. International Journal of American Linguistics, 29.

- Licht, Daniel Aguirre. (1999). Embera. Languages of the world/materials 208. LINCOM.

- Mortensen, Charles A. (1999). A reference grammar of the Northern Embera languages. Studies in the languages of Colombia (No.7); SIL publications in linguistics (No. 134). SIL.

- Pinto García, C. (1974/1978). Los indios katíos: su cultura - su lengua. Medellín: Editorial Gran-América.

- Rendón G., G. (2011). La lengua Umbra: Descubrimiento - Endolingüística - Arqueolingüística. Manizales: Zapata.

- Rivet, Paul; & Loukotka, Cestmír. (1950). Langues d'Amêrique du sud et des Antilles. In A. Meillet & M. Cohen (Eds.), Les langues du monde (Vol. 2). Paris: Champion.

- Sara, S. I. (2002). A tri-lingual dictionary of Emberá-English-Spanish. (Languages of the World/Dictionaries, 38). Munich: Lincom Europa.

- Suárez, Jorge. (1974). South American Indian languages. The new Encyclopædia Britannica (15th ed.). Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Swadesh, Morris. (1959). Mapas de clasificación lingüística de México y las Américas. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- Tovar, Antonio; & Larrucea de Tovar, Consuelo. (1984). Catálogo de las lenguas de América del Sur (nueva ed.). Madrid: Editorial Gedos. ISBN 84-249-0957-7.

External links

[edit]- Proel: Familia Chocó